16. Nap Rucker

Nap Rucker played an even ten seasons with Brooklyn (1907-16), back when the franchise had intriguing team names like the Superbas and the Robins.

Rucker only had a career record of .500 (134-134), but it was not until 1915 that he played on a winning team. In his first seven seasons, Rucker's ERA was below 3.00, and he was always in the top ten in bWAR for Pitchers in those seasons. Rucker was at the top of that leaderboard in 1911 and 1912.

Considered to be one of the fastest pitchers of his day, Rucker was again in the top ten in Strikeouts in those first seven seasons, and while he was prone to fits of wildness, he still managed to place in the top ten in WHIP four times.

Rucker's last three seasons were mostly ineffective from arm fatigue, and he was out of the Majors by age 31. As good as Rucker was, it could be argued that it was wasted for bad Brooklyn teams, but he gave fans a great reason to come out to the park.

8. Zack Wheat

Zack Wheat was one of the top players for Brooklyn in the dead ball era, playing all but his last season in the Majors for Brooklyn.

Playing in the Outfield, Wheat first appeared for Brooklyn in 1909, becoming their starting Leftfielder the year after. Collecting 2,804 of his 2,884 Hits with the Dodgers, Wheat batted .317 for the team and was also a solid defensive player. Wheat regularly batted over .300, winning the 1918 Batting Title, and was the Slugging Champion in 1916.

Had Wheat played decades later in the Dodgers heyday, he would be more remembered in the baseball zeitgeist.

Wheat entered the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1959 through the Veteran’s Committee.

7. Pee Wee Reese

How do you not love somebody named Pee Wee Reese?

The Dodgers fans did, we do, and as of this writing, it is Reese who is the all-time franchise leader in bWAR for Position Players.

We bet that was a surprise!

Reese was coming up through the Red Sox system and should have been the heir apparent at Short for Boston. The problem was that Boston had Joe Cronin at that position, who was also the Manager, and he suggested that Reese be traded, which happened in the summer of 1939. Reese was called up to his new parent club, Brooklyn, the following year, and he broke through in 1942, making his first All-Star team while finishing first in Defensive bWAR.

Reese was one of the many American players to leave the game due to military service stemming from World War II. He came back better than ever in 1946, ascending back to the top of defensive infielders, but now he was a much better hitter. Reese was also a key figure in accepting Jackie Robinson, as Reese refused to sign a petition from other teammates to keep him from being called up. Not only would Reese and Robinson become friends, but his public displays of acceptance also showed the world that the Negro League players would be welcomed.

From 1946 to 1954, Reese was an All-Star, batting at least .260 and drawing a sizable amount of Walks. He was not a potent power hitter, but he could go deep, hitting 126 over his career, combined with excellent speed (232 Stolen Bases). The overall package gave Reese eight top-ten MVP finishes, peaking at fifth in 1949. Reese would help the Dodgers win the 1955 World Series, but age would reduce his effectiveness afterward, and he retired after the 1958 Season.

He retired with 2,170 Hits and batted .269. He would not enter the Baseball Hall of Fame until 1984 when it took the Veteran's Committee to select him. Los Angeles then retired his number 1.

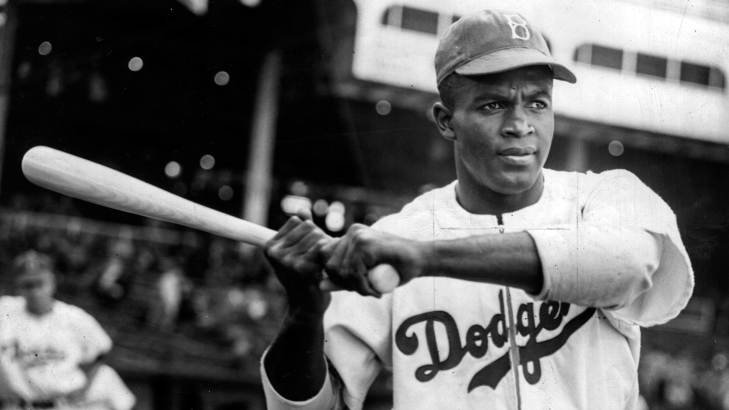

2. Jackie Robinson

If this list were based purely on iconic stature, Jackie Robinson would be number one, and it wouldn't be close. The same would be true if we looked at importance. Saying that this is the Los Angeles Dodgers, one of the most successful teams in all of sports, and there are many Hall of Fame Dodgers who logged more playing time and compiled more stats than Robinson did while wearing the Dodger blue. This has to matter.

There is nothing we can write about Robinson that you have not heard before. Dodgers General Manager, Branch Rickey, wanted to break the color barrier and needed the right player to do it. He was a player who was not only great but could withstand the barrage of hatred coming his way. That man was Robinson.

After a year in the Minors to get him mentally ready, Robinson debuted for Brooklyn in 1947 at the age of 28. Robinson proved what Rickey already knew in that he was a five-tool player who could handle the mental stress of being the first black man in the Majors. Robinson won the Rookie of the Year and was entering his peak.

In 1949, Robinson again made history by becoming the first black player to win the MVP while also capturing the Batting Title. It was his only MVP, but he received MVP votes the next four years, and he never finished a year batting under .300 until 1955. Robinson had the power (137 HR) and the speed (197 SB), batted over .300 for his career, and was also one of the best defensive players of his day.

Robinson's age and injuries caught up with him in 1955, but his leadership skills were invaluable to a team that won the World Series that year. He retired after the 1956 season, which would essentially void a trade to the Giants, and his career ended as one of the most-known athletes of all time, a status still enjoyed today.

The Baseball Hall of Fame inducted Robinson in his first year of eligibility in 1962. Major League Baseball would later league-wide retire his number 42, the number that he will own forever.

6. Dazzy Vance

The ranking of Dazzy Vance might seem a little high, but much of that stems from Vance being successful for the Dodgers when they were not one of the better teams in the National League. That should not matter, as, at one time, he was the elite Pitcher in the NL and the top flamethrower for years.

Vance bounced between the Minors and Majors for a few years before securing a spot in the Brooklyn rotation in 1922, his first entire season at the elite level. Vance, who was 31, was an older rookie but still led the NL in Strikeouts (134), and while he was at an advanced age for a baseball player, he was about to begin a period of greatness.

Vance led the NL in Strikeouts the next six years, three of which would see the hurler exceed 200. He led the league in Wins in both 1924 and 1925 and was a three-time leader in ERA. He won the National League MVP in 1924 and became the first Dodger player to capture the award. Throughout the 1920s, no Pitcher had a better SO/BB than Vance, who became the Majors first, seven-time leader.

The Pitcher was traded to St. Louis before the 1933 Season, concluding an impressive run in Brooklyn, considering it was all in his 30s. Vance had a record with Brooklyn of 190 and 131, a 3.17 ERA, and 1,918 Strikeouts.

Vance entered the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1955.

5. Duke Snider

The Brooklyn Dodgers put together a potent lineup in the 1950s that would feature a collection of future Hall of Famers and legends. If we hold that true, then let’s remember that the man who batted third in this lineup for years was Duke Snider, the power man of a power team.

Snider came up through the ranks with fellow legend Jackie Robinson, and though he fell behind Robinson in fame overall, his performance as a Dodger arguably eclipsed his teammate. Becoming a starting Outfielder in 1949, "The Duke of Flatbush" might have succumbed to a high share of Strikeouts, but he positioned himself as one of the top power hitters in the 1950s.

A perennial All-Star from 1950 to 1956, Snider had a rough start to that streak, as he was routinely criticized in the last half of the 1951 Season when he slumped the Dodgers blew a 13 Game lead to the Giants. He overcame the lousy press to blast 40 Home Runs in four straight years (1953-56), winning the Home Run Title in '56 (43) while also leading Brooklyn to a World Series win. Throughout this 1950-56 run, Snider also captured the 1955 RBI Title (136), won two Slugging Titles and two OPS Titles, and was in the top ten in MVP voting five times.

As the Dodgers moved west to Los Angeles, Snider's skills eroded, but he still helped them win the World Series as an elder statesman and dugout leader. His contract was sold to the expansion New York Mets in 1963, reuniting him with his fanbase in New York City.

Snider overall accumulated 1,995 Hits, 389 Home Runs, and 1,271 RBI while batting .300 as a Dodger. He entered the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1980, and Los Angeles retired his number 4 the same year.

3. Sandy Koufax

One of the many players we could have easily inserted as the greatest Dodger of all time is Sandy Koufax, and had we done this list two years before its first publication (2022), he likely would have been.

Koufax was a walk-on at the University of Cincinnati, and while he showed poor control, he had the velocity. The southpaw was scouted by the Dodgers and was signed by them in late 1954, and his sheer talent propelled him to the Majors the following summer, but the first half of his career was not what got him into the Hall of Fame.

It was widely believed that Koufax was the hardest thrower in the game, but the accuracy wasn't coming, and when he got in trouble, the more erratic he became. From his debut to 1960, he had a losing record of 36-40 with an ERA of 4.10 and a WHIP of 1.428. Koufax and the Dodgers knew the talent was there, but he grew frustrated and considered quitting. He opted to give it one more year, with Koufax giving his all, dedicating himself to improved fitness. More importantly, one of the Dodgers' scouts noticed that he reared back so far that he lost sight of the plate. These corrections made Koufax the most feared Pitcher of the next six years.

1961 would be his breakout year, with Koufax going 18-13 with a league-leading 269 Strikeouts and topping the NL in FIP (2.00) and SO/BB (2.80). Koufax was an All-Star this year, beginning a six-year streak, the first of many. Koufax won his first ERA Title in 1962 (2.53) and WHIP Title (1.036), starting a five-year run and a four-year, respectively, as the league leader. The first two seasons of the 1960s were terrific, but it was about to get even better.

It can be debated that the next four years were the best ever by a Pitcher. Not only did he keep his ERA under 2.05 in all those years, but his WHIP also stayed under one. Koufax led the NL in three years (1963, 1965 & 1966), and he won the Cy Young in all of those seasons, with a third-place finish in 1964. He also won the MVP in 1963 and was the runner-up for the award in 1965 and 1966.

Koufax, who had already won a World Series Ring in 1959, led Los Angeles in 1963 and 1965, going a combined 4-1 and allowing four Earned Runs over 42 Innings with 52 Strikeouts. He won the World Series MVP in both of those playoffs, and while the teams were loaded with talent, it is difficult to envision the Dodgers winning ’63 and ’65 without Koufax.

As great as Koufax was from 1963 to 1966, traumatic arthritis forced him to retire. Koufax was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility, and at the age of 37, he was (and still is) the youngest man to enter the Hall. Los Angeles retired his number 32 in 1972, which should have happened much sooner.

4. Don Drysdale

You could say that Don Drysdale was in the shadow of Sandy Koufax for most of his career, and there is nothing wrong with that. Koufax was a special player in his second half, and no other practitioner of the mound in the 1960s first half-decade would not have been his second fiddle. Shadow or no shadow, Drysdale was a special Pitcher on an exceptional team and worthy of this top-five rank.

286. Preacher Roe

Preacher Roe played a whopping 2.2 Innings for the St. Louis Cardinals in 1938, and he went back to the minors for the next five years before being traded to the Pittsburgh Pirates organization. The Pirates called him up, and at age 28 in the World War II depleted Majors, he had his second chance.

226. Babe Herman

Babe Herman made his first appearance in the Majors with the Brooklyn Robins, and it was there where he established himself as one of the better power hitters in the National League.

275. Eddie Stanky

There is a trope in all sports where athletes have been described as making the most of their limited athletic skills. Eddie Stanky certainly fits this bill.

155. Jimmy Sheckard

Jimmy Sheckard spent most of his career with either Brooklyn or the Chicago Cubs, and while they were both high-profile teams, Sheckard is one of the most undervalued players in history.

189. Jake Daubert

A 15-year veteran of the Majors, Jake Daubert played for two different teams in his Major League career, the Brooklyn Superbas/Robins and the Cincinnati Reds.

210. Jack Fournier

Jack Fournier was a Manager’s enigma. He could hit well, but his fielding was so bad, that in the era before the Designated Hitter that the talented batsmen would have spells where he could not make the Majors.

185. Dixie Walker

Fred "Dixie" Walker was in the New York Yankees organization for a few years, but he struggled to stay in their lineup. The Yanks waived him, and the White Sox picked him up during the 1936 Season, and the year after, he had his breakthrough campaign in the Majors.

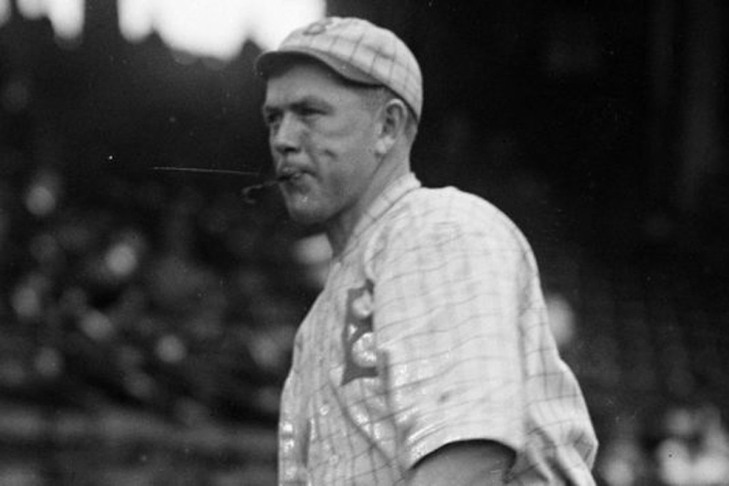

234. Nap Rucker

Nap Rucker played an even ten seasons with Brooklyn (1907-16), back when the franchise had intriguing team names like the Superbas and the Robins.

91. Don Newcombe

Don Newcombe was more than a great Pitcher, as he was a trailblazer in terms of African Americans in baseball.

160. Dolph Camilli

Dolph Camilli came up with the Chicago Cubs, and they arguably gave up as he was prone to the Strikeouts, and he was traded to the Philadelphia Phillies. With Philly, he still struck out a lot but was developing a strong power game. In 1935, through 1937, the First Baseman would have at least 25 Home Runs, and in the latter two years, he would bat over .310. In that last season, Camilli would have a league-leading On Base Percentage (.446).