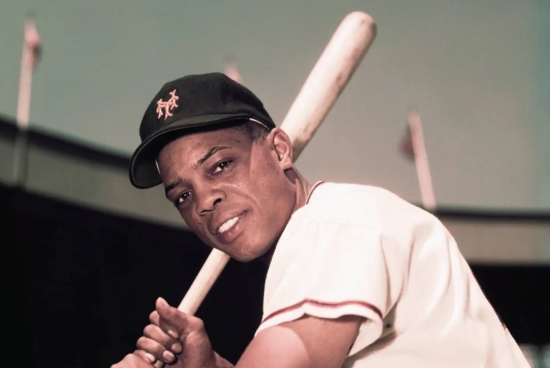

The Say-Hey Kid in his prime, back when the Giants were still playing in New York. Now Willie Mays will always reside on another, higher plane of existence.

Certainly that has been the case for me. Living my first few years in Canada, in 1969 we moved to Kuwait for my father's job; then, two years later, we came to the United States when I was eight. With precious little memory of television in Canada, and with precious little television to watch in Kuwait, I was gobsmacked by American pop culture upon arrival in the States, staring open-mouthed at the TV for hours, dazzled by the sheer quantity and variety of it all. Somewhere within that electronic smorgasbord I discovered a baseball game. Watching that game, I decided that I liked baseball.

Never mind that I still had to learn how baseball was played. That mystery began to unravel when, after a year living in New Jersey, we moved to the San Francisco Bay Area in what is now known as Silicon Valley. I began to play baseball, and when the youth activities team at the local community center offered an excursion to see the San Francisco Giants play a day game at Candlestick Park against the San Diego Padres, I signed up to see it.

It was my first Major League game although I don't remember anything about it despite everyone being all atwitter about Willie McCovey being back in the Giants' lineup. The Giants' other Willie, Willie Mays, had been traded to the New York Mets earlier in the 1972 season. For one thing, we had upper-deck seats, so not only did it seem like we were a mile up in the air but the field seemed to be a mile away too. For another, we were a group of schoolkids who chattered incessantly and hardly paid attention to the game. If I've identified the correct game (thank you, Baseball Reference), apparently I saw future Hall of Famer Juan Marichal get roughed up early in a 5–2 loss although Stretch, the Dominican Dandy's fellow Cooperstown alumnus, did hit a solo home run to get the Giants on the board.

Later that year, with my zeal for baseball becoming more pronounced, I saw the Giants play the Atlanta Braves at Candlestick in the only baseball game my father ever took me to, possibly in an effort to shut me up about baseball. It was a good thing we went because we were two of only 3,042 fans in attendance even though legendary Hank Aaron was in the lineup for the Braves. (He singled, walked, and scored a run in five plate appearances.) Facing each other at the end of the year, both teams had long been eliminated from the postseason.

This game I do remember, at least to some degree: Both Gary Maddox and Gary Matthews homered for the Giants, although in looking at the box score, Dave Kingman also went deep to spark a six-run bottom of the fifth as the Giants went on to clobber Atlanta 14–3. Also in the game were Bobby Bonds for the Giants and Dusty Baker for the Braves. (Years later, on my fortieth birthday, my ex-wife Kathy took me to an Anaheim Angels game against the Baltimore Orioles. In the lineup playing center field for the Orioles was Gary Matthews, Jr. Already feeling old, I turned to her. "You know, I saw his father play when I was a kid.")

That game cemented my love for the San Franciso Giants, which continues to this day. Back in school, I couldn't wait for the Scholastic Book Services catalog, offering books written for "young readers" on a cornucopia of subjects, to make its way around the classroom every month. I got books on everything from icebergs to World War One flying aces to US presidents, which my parents were willing to buy because they were educational, but I also snuck in my share of sports biographies ranging from basketball's "Pistol Pete" Maravich to football's O.J. Simpson and Roger Staubach to baseball's Tom Seaver. I also got a book titled The Baseball Life of Willie Mays by Lee Greene.

My introduction to Willie Mays, back when I was a kid.

I can't tell you how many times I read that biography of Willie, nor can I tell you why I read it so many times. I just did. All I can say is that something in Willie's story resonated with me at that early age, even if, despite its writing to young readers, I still didn't understand it all.

For example, Greene recounts when Mays was called up to the then-New York Giants in 1951. When Mays told manager Leo Durocher that he didn't think he was ready for the Major Leagues, Durocher asked him what he was batting for the Giants' farm team the Minneapolis Millers. Mays replied that he was hitting .477, which managed to silence Leo the Lip until, as Greene delicately put it, he swore into the telephone. It wasn't until years later that I realized that a .477 batting average is an unreal number even in the minors, and today I'd say that a lot of Major League hitters would kill to have a .477 slugging average, let alone batting average. (Mays wasn't so auspicious when he first got to the Majors: In his first seven games, he got one hit in 26 at-bats; at least his first hit was a home run off future Hall of Famer Warren Spahn.)

Willie hits one sometime during his 1951 rookie season. He would go on to thrill baseball fans for another two decades.

Still, I understood enough to intuit that Willie Mays was an extraordinary baseball player. And like so many kids, I wanted to be like him. A lasting childhood resentment is that, for whatever reason, my parents wouldn't let me play Little League Baseball even though all my friends were playing, so I never received any formal instruction or got to play organized ball. Despite that, I still loved to play on the sandlot and during PE along with bouncing the ball off the wall if I couldn't convince anyone to play catch with me.

Despite not being any good, I still insisted on playing center field whenever I could get away with it because, of course, you-know-who played center. But regardless of where I played, I still got groans whenever I couldn't catch the ball, which was just about all the time. Then came that one game during PE in grade six when, out in center, the ball was hit to me. Already my teammates were groaning as the ball sped toward me. I stuck out my mitt. I caught it. Those groans turned instantly to cheers, as incredulous as they were. From that day on, I never looked back.

Well, at least as far as catching the ball went, I didn't. I still couldn't hit the ball out of the infield until I was in my teens, and it wasn't until my thirties and playing in a slow-pitch softball league that the coach of our team, who had played college ball, once remarked that I had "a cannon for an arm." But once I learned to catch the ball, I could get a good read on it off the bat, get to it quickly, and catch it. No longer did anyone have an issue with my playing center, and opposing hitters learned not to hit it to me because they knew their potential hit would die in my glove.

Tom Wolfe, author of The Right Stuff, once wrote a fiction piece called "The Commercial: A Short Story," a satire on athletes' product endorsements featuring an African-American baseball player named "Willie Hammer," a thinly-disguised portrait of Hank Aaron although someone like Willie Mays might also fit the profile of the seemingly inarticulate ballplayer ill at ease with making a television commercial. Through Willie Hammer, Wolfe notes that:

This country is full of about 100 million men who played a little ball, some sport, some time, some place. And wherever it was, it was there they left whatever feeling of manhood they ever had. It grew there and it bloomed there and it died there and now they work at some job where the manhood thing doesn't matter, and the years roll by. But they've got this little jar of ashes they carry around . . . "I once played a little ball . . . " They see a professional athlete, and it stirs up the memories . . . They can feel the breeze.

That's my little jar of ashes, that Willie Mays inspired me to play center field even though I didn't even get to put on Little League uniform, a desperate attempt to show that I existed in the same universe as him although we were light-years apart. However puny or pitiful, that childhood totem remains, and I expect that it always will even though Willie is now gone.

In my early teens, I was introduced to Superstar Baseball!, a statistical-simulation board game that boasted of having "96 of the greatest all-time players in Major League history!" or some such breathless claim. Compared to current video games, it looks hilariously antiquated now, using rolls of the dice to spur the "action" that, besides the abstraction of the playing board, took place in the imagination. But more than anything else, it spurred my understanding of baseball analytics and history.

Naturally, I always had to have Willie on my team. As corny as it sounds, my pulse did quicken every time he came up to bat. When I played solitaire games, I would occasionally find myself rolling the dice for him again if he made an out just because it was Willie. It was cheating worse than steroids, but I couldn't help myself.

Back in Canada during grade ten, I bought a Mays autobiography in a used-book store called Willie Mays: My Life In and Out of Baseball that was co-written with Charles Einstein. This was definitely written for an adult audience, and, first published in 1966, while he was starting his decline phase, it wasn't as candid as Jim Bouton's landmark 1970 exposé Ball Four although it was hardly as upbeat as The Baseball Life of Willie Mays.

The adult version of Willie's life in and out of the spotlight. Turns out he's a human being just like the rest of us. Well, on the baseball field might be another story.

In fact, what I remember is Mays grousing about the reactions he got from the San Francisco fans following the Giants' move from New York after the 1957 season. No longer the Gotham Golden Boy, Mays watched the West Coast fans instead embrace new recruits Orlando Cepeda, who sadly died ten days after Willie, and Willie McCovey. During one slump in which Mays seemed to be popping out a lot, one fan got under his skin. "Here Comes Pop-Up Mays," the fan derided every time Mays came to the plate.

Perhaps that was the watershed for what "hero worship" I had, particularly regarding athletes, because as I headed into adulthood my interests and priorities changed. My childhood love of baseball had dissipated by the 1980s although I still recall vividly the 1979 World Series and the Pittsburgh Pirates' comeback from a 3–1 deficit against the Baltimore Orioles and the heartbreak that was the 1986 World Series, which stirred my affection for the Boston Red Sox in their legendary loss to the New York Mets.

Baseball had essentially disappeared from my consciousness for more than a decade, leaving Willie Mays a seeming childhood affectation. It flickered to life again in the 1990s, first when, as a native-born Torontonian, I watched with great interest the Blue Jays' back-to-back world championships in 1992 and 1993.

Then, although I have been a long-time resident of Orange County, California, but had never gone to see the local team the Angels play, I ventured into Angel Stadium in 1997 only because that was the year that interleague play was introduced—and the Giants had come to town. In the lineup for San Francisco were Rich Aurilia, whom, as I later learned, I witnessed hit the first grand slam in interleague play history; Jeff Kent, whom I have plugged, endlessly and so far in vain, as worthy of the Hall of Fame; and Barry Bonds, Willie Mays's godson, whose travails in trying to get into Cooperstown are probably the most notorious sports saga in recent memory.

This was my first in-person MLB game since I saw Hank Aaron play in Candlestick Park a quarter-century previously, and it sparked my renewed interest in baseball. Of course, as a man entering middle age, I viewed baseball through a very different lens, more detached and analytical, with a more critical eye toward its history.

This didn't mean that I lacked any emotion for baseball, such as Kathy and I whooping it up so much after the Arizona Diamondbacks won Game Seven against the hated New York Yankees (now also a Red Sox fan, remember) in the 2001 World Series that our cat Tabitha rushed over to meow frantically at us because we were completely freaking her out, or the heartbreak of both the Giants' seven-game loss to the Angels in the next year's World Series and the Red Sox' seven-game loss to the Yankees in the 2003 American League Championship Series, which then led to the rollercoaster ride of the 2004 ALCS rematch with New York and the eventual four-game sweep of the St. Louis Cardinals in the World Series that broke the Curse of the Bambino.

Through it all, Willie Mays remained in the background but never far from my memory—or from my heart. When the analytical revolution began producing advanced defensive statistics such as defensive runs saved, and Andruw Jones topped the list for center fielders, my immediate reaction was, "No way. No one could ever be as good, let alone better, than Willie." As Barry Bonds made his way up the career home run list, I had mixed feelings as he passed his godfather on his way to the top. (And my biggest in-person sports moment was seeing Bonds hit Number 755 to tie Hank Aaron in August 2007.) Those feelings became less mixed—meaning they were more defensive toward Willie—when Álex Rodriguez, then Albert Pujols, passed him.

But perhaps the most striking quality about Willie Mays in recent years is how much he began to look like my father. What always struck me were the puffy black bags under his eyes—they were dead ringers for my father's. Although Willie was African-American and my father was of East Indian descent, they had the same dark-brown skin tone, and as both aged (both at roughly the same time: my father was born two years before Willie), their faces got puffier as their bellies got rounder. (And as I look in the mirror, to my dismay I see that I am my father's son.)

Willie Mays well into his retirement. Not only did he look a lot more human, he also looked a lot like my father.

There is where the resemblance ends. In fact, my father, born and raised in Trinidad, had an animosity toward blacks, or at least Afro-Trinidadians, those who had come to Trinidad from African nations and, by the 1970s, had usurped Indo-Trinidadians like him as Trinidad's dominant power faction; it was an animosity almost as vehement as his anti-Semitism. (In case you don't think that persons of color can be bigoted or racist. Thankfully, I am not my father's son in that respect.)

My father took me to one baseball game and played catch with me once. That is what it is. My father was of that generation, perhaps a little older (he was 35 when I was born), that was more distant from their children both physically and emotionally. You reap what you sow. My father provided for us, even, because of his job, enabled us to live and travel throughout the world; he never abandoned us; and he put up with my various and many "youthful indiscretions" better than many other men might.

When my mother died in May 1992, we watched the World Series together later that year. My father, although a sports fan, was never a baseball fan; it was more the Toronto connection than the Blue Jays connection. Although we never bonded over it, it was something we could share, and we came back the next year to see the Blue Jays repeat. In a sense, it might be similar to the catch-with-dad moment in Field of Dreams that still makes grown men weep like babies although I've never understood why men still fall for that fabricated glurge.

Have I gotten too far from Willie Mays? Am I making this all about myself? In a sense, yes. But that usually happens with a death in the family. I never met Willie Mays. I never even got to see him play in person. Yet from when I first read The Baseball Life of Willie Mays, I must have felt that he was part of my family, a distant relative one knows only by reputation. In that respect, Willie had many distant relatives, all of whom are mourning our loss.

On his birthday this year, I watched the MLB Network's rebroadcast of a 2010 interview Willie did with Bob Costas before a live studio audience that I don't recall seeing previously. He was warm, sometimes charming, sometimes a little defensive, alternately self-deprecating yet assertive about his abilities as he joshed with Costas.

Above all, he was respectful and appreciative of the audience. Willie always knew he was an entertainer, and he was often quoted as saying that the fans came out to see a show—perhaps a reflection of his early, brief, but apparently influential start with the Birmingham Black Barons in the Negro Leagues—and he always strived to give them that show. Famously, he wore a cap that was one size too small, so that when streaked around the bases, or sprinted to chase down a fly ball, it flew off his head, the flourish to his extraordinary prowess that wowed the crowd.

I've never agreed with conservative commentator George Will on practically anything, but I do admire him for the observation he made about Willie Mays in the mammoth Ken Burns documentary Baseball, undoubtedly my favorite moment:

What is truly amazing is that it never looked like work from the way he did it. That is what made him so extraordinary: Willie Mays was the consummate five-tool player. He made everything he did—run, throw, field, hit for average, hit for power—look so effortless. That is the mark of the great ones. They make it look so easy that you're sure you can do what they do. Until you try it. And with Willie, he not only did everything effortlessly, he did it with flair, with an eye toward the audience, giving them a performance they might not ever forget. (Exhibit A: "The Catch" in Game One of the 1954 World Series.)

A catch as immortal as he is. Willie Mays robs Vic Wertz of a hit in Game One of the 1954 World Series. His throw back into the infield was just as spectacular. Of course.

Unlike Hank Aaron or Frank Robinson, certainly unlike Jackie Robinson or Larry Doby or Curt Flood, Willie Mays didn't speak explicitly about the civil rights movement during or after his career. As a black Southerner from Alabama, he was directly affected by segregation and was in the thick of baseball's long struggle toward integration. He was criticized for that, particularly since he was a superstar whose opinion, like it or not, did carry more weight than most.

During the Bob Costas interview, he did seem most defensive, or at least self-conscious, about that. In the end, Willie Mays might have felt that his play was his speech, that by excelling in a sport that had barred those of his race from participating he was speaking by example. By that measure, he was the most eloquent speaker ever. But that's my bias.

When Willie announced on June 17 that he wouldn't be able to attend the Negro Leagues tribute at Rickwood Field in Birmingham, Alabama, I sensed that it might be a portent. He died the next day. Yes, it's easy to say that after the fact. But I had watched the Bob Costas interview on May 6 wondering if perhaps his time was coming soon.

Say Hey has gone away. What is there to say? You were always an immortal, Willie Mays. And you truly are now.

Comments powered by CComment