Our All-Time Top 50 Los Angeles Dodgers are now up!

Yes, we know that this is taking a while!

As many of you know, we here at Notinhalloffame.com are slowly generating the 50 of each major North American sports team. We have a new one to unveil today, that of the Los Angeles Dodgers.

One of the most celebrated franchises in all sports, the Los Angeles Dodgers were initially the Brooklyn Grays in 1883, but it was a long time before they found an identity.

The organization changed its name multiple times since its origin, the Atlantics (1884), back to the Grays (1885-87), then the Bridegrooms (1888-90), the Grooms (1991-95), the Bridegrooms again (1895-98, the Superbas (1899-1910), the Trolley Dodgers (1911-12), then the Dodgers (1913), the Robins (1914-1931), before settling on the Dodgers again in 1932.

The Brooklyn Dodgers would sign Jackie Robinson to integrate baseball, and in 1955, on their eighth attempt, they finally won their first World Series.

The fans of Brooklyn were not rewarded for their loyalty and patience, and like the crosstown New York Giants, westward the Dodgers went in 1957, where they remain to this day.

In Los Angeles, the Dodgers won three World Series Titles in their first ten years in the new environment, capturing it all in 1959, 1963, and 1965. The 1970s saw them competitive at the decade's end, and they won two more Championships in the 1980s (1981 and 1988).

In recent years, the Dodgers have been a top team, with their last World Series win coming in 2020, giving them seven in total.

Our Top 50 lists in Baseball look at the following:

1. Advanced Statistics.

2. Traditional statistics and how they finished in the National League.

3. Playoff accomplishments.

4. Their overall impact on the team and other intangibles not reflected in a stat sheet.

Remember, this is ONLY based on what a player does on that particular team and not what he accomplished elsewhere and also note that we have placed an increased importance on the first two categories.

This list is updated up until the end of the 2022 Season.

The complete list can be found here, but as always, we announce our top five in this article. They are:

1. Clayton Kershaw

2. Sandy Koufax

4. Duke Snider

5. Dazzy Vance

We will continue our adjustments on our existing lists and will continue developing our new lists.

Look for our more material coming soon!

As always, we thank you for your support.

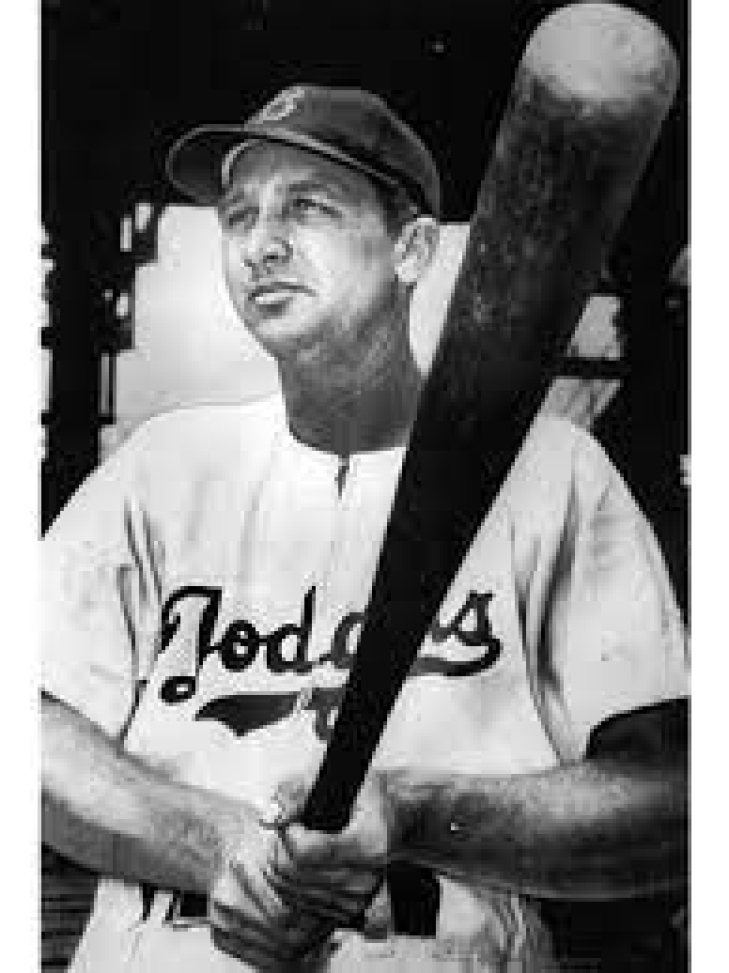

49. Babe Herman

The first six seasons (1926-31) of Babe Herman’s career were an impressive blend of Batting Average and power, leading to high popularity among the Robins fans.

Herman debuted in 1926, becoming an everyday player as a rookie, and he was a good batter with a .319, 35 Doubles, and 11 Home Runs. Dropping to .272, Herman went on a three-year streak where he batted at least .340. As good as he became as a hitter, he was also known for his eccentric behavior and basepath blunders; he twice stopped to watch Home Runs go over the wall and was passed on the basepaths, and once failed to watch what was happening ahead of him, leading to three men on Third Base.

Regardless of Herman's daffiness, he was still a player who batted .381 in 1929, and in 1930, he broke that by batting .393 with career-highs in Home Runs (35) and RBIs (130), and astoundingly, he never received a single Hall of Fame vote. Herman dropped to .313 in 1931 and was still very good offensively, but the Robins looked to go in a different direction and traded Herman to the Reds after the season.

Had Herman been a better defensive player (he never had a season with a positive Defensive bWAR in Brooklyn and was often error-prone), he would be ranked much higher, but as it stands, he was a very good player at a time when Brooklyn did not have much.

As a Robin, he batted .339 with 1,093 Hits and 112 Home Runs.

48. Pete Reiser

"Pistol" Pete Reiser might be one of the biggest "what could have been" in Dodger history, as very few players on the diamond lost greatness so quickly due to injuries.

Reiser was pegged to be a star by St. Louis Cardinals management, and they were dismayed when he was one of the Minor League players that Commissioner, Kennesaw Mountain Landis, deemed free agents. Cardinals GM, Branch Rickey, had an agreement with the Dodgers, who signed Reiser to trade him back to St. Louis, but Brooklyn Kept Reiser, and Rickey, himself, would join Brooklyn in 1943.

Reiser made it to the parent club in 1940, appearing in 58 Games, but he was an everyday player in 1941 and had one of the most explosive campaigns in Dodgers history. He led the NL in Runs (117), Doubles (39), Triples (17), Batting (.343), Slugging (.558), OPS (.964), and bWAR for Position Players (8.0), but was jobbed out of the MVP to Home Run and RBI leader, Dolph Camilli, who was also his teammate. Brooklyn won the Pennant that year but was crushed by the Yankees in five.

Reiser had an interesting 1942, again going to the All-Star Game, but mid-season, he suffered a concussion when he crashed face-first into the outfield wall. He returned but was not the same player for the rest of the season.

Like many other Americans, Reiser served in the U.S. Military and missed three years, but a shoulder injury in an army baseball game hampered his batting. Reiser was still the same player regarding effort, but the oft-injured Outfielder never came close to what he was in 1941. He was traded to the Braves after the 1948 Season, ending his Dodgers run.

Reiser compiled 666 Hits with a .306 Batting Average.

39. Mike Griffin

Mike Griffin was already playing in top baseball leagues for four years, last playing a season in the short-lived Player's League for Philadelphia. The Outfielder joined Brooklyn in 1891 of the National League, the final team he would play for.

Griffin had a great start with the Bridegrooms, leading the NL in Doubles (36) with 65 Stolen Bases. Swiping at least 30 Bases each of the next three years, Griffin began a five-year streak in 1894 where he batted at least .300, which concluded in 1898. To his surprise, Brooklyn merged with Baltimore, and he refused to sign a contract under the new Manager, Ned Harlon. His contract was sold to Cleveland, who then transferred his contract to St. Louis. Griffin would never play again but did win a lawsuit against Brooklyn for money he felt owed $2,300.

His end with Brooklyn was not pretty, but his play was solid, with a .305 Batting Average, 1,168 Hits, and 264 Stolen Bases.

43. Preacher Roe

An All-Star with the Pirates in 1945, Elwin “Preacher” Roe made the most of his belated opportunity with the depleted World War II roster, but when the Majors were replenished, the next two years saw his ERA balloon over five, though likely this was the result of the after-effects of a fractured skull he suffered from a fight while refereeing a high school basketball game. Now over 30, it appeared that Roe’s run in the Majors would end shortly, but Dodgers GM, Branch Rickey, had other ideas.

Now a Dodger, healthy, and using an illegal spitball, Roe became a star in their rotation. Roe went to four consecutive All-Star Games (1949-52), peaking with a 22-3 record in 1951, where he was fifth in MVP voting. Brooklyn were contenders, and he helped them win three Pennants (1949, 1952 & 1953), and though there were no Titles in Roe's resume, he had a 2-1 post-season record with a 2.54 ERA.

Age and fatigue caught up to the Preacher, and he never played for Baltimore, the team he was traded to after the 1954 Season. His pitches were slow, but he generated outs for Brooklyn and gave them a scintillating record of 93-37.

41, Jimmy Sheckard

Jimmy Sheckard played for Brooklyn on three different occasions; though this was in a tight vacuum, you could argue that his first MLB half was indeed with Brooklyn.

Sheckard first appeared for Brooklyn in 1897, becoming a starting Outfield as a sophomore, but he was assigned to the first version of the Baltimore Orioles in 1899, only to be re-assigned back in 1900. He had a very good 1901, putting up career-highs in Hits (196), Triples (19), and the Slash Line (.354/.409/.534), with his total in Triples and Slugging league-leading.

The year after was a little strange, as Sheckard again joined the Orioles (the second incarnation), but it only lasted a handful of Games before he jumped back to the Giants, and had another excellent year in 1903, where he led the NL in Stolen Bases (67) and Home Runs (9), making him the first player to lead the league in those categories.

Traded to the Chicago Cubs after the 1905 Season, Sheckard would win two World Series Titles with the Cubs. With Brooklyn, Sheckard compiled 966 Hits with a .295 Batting Average and 212 Stolen Bases.

36. Brickyard Kennedy

William “Brickyard” Kennedy played for Brooklyn in the first ten (1892-1901) of his 12 years in the Majors, where he won a lot of Games, though he would not dazzle with other statistics.

A four-time 20-Game winner, Kennedy had a very good record for Brooklyn of 177 and 148, but his ERA for the team was 3.98, including a 5.05 year where he still had a 19-12 record. Still, Kennedy did enough to keep his team in games, and Brooklyn batters had enough confidence that he could keep them competitive. He also helped his cause with his offense, batting .256 with 306 Hits in Brooklyn.

Kennedy’s overall numbers may not hold up, but his 177 Wins are still fifth all-time in franchise history, and that means something!

46. Whit Wyatt

Before Whit Wyatt joined the Brooklyn Dodgers, he had already played nine years in the American League (Detroit, Chicago & Cleveland), but he played the entirety of the 1938 Season in the Minors. The Brooklyn Dodgers still thought there was life left in Wyatt’s career, and they purchased his contract from Cleveland. As was often the case in this era, the Dodgers were proven right.

Wyatt, who had never been to an All-Star Game before (or anywhere close), went to Mid-Summer Classic in all his first four years in Brooklyn, the best of which was in 1941. That season, he led the NL in Wins (22), had an excellent 2.34 ERA, and led the league in FIP (2.44), WHIP (1.058), and SO/BB (2.15). Wyatt was third in National League MVP voting and would have been the Cy Young winner had that trophy existed. The Dodgers won the Pennant that year, with Wyatt playing a massive part in that accomplishment.

Wyatt had two more strong years in Brooklyn, obtaining MVP votes in both years, but age caught up with him, and the Dodgers sold his contract to the Phillies, where he never won a Game.

Wyatt had an ERA of 2.86 with an 80-46 Record with Brooklyn. That might be 80 more Wins than many baseball writers thought he would do.

33. Jeff Pfeffer

Jeff Pfeffer was a very good Pitcher for Brooklyn in the 1910s, who, from 1913 to 1914, was one of the more competent players on the mound in the National League.

Pfeffer had only played seven Major League Games before the 1914 Season (two were with the St. Louis Browns in 1911), and would have likely won the 1914 Rookie of the Year, had there been one. This began a three-year run as a top Pitcher, where he went 66-37 with a 1.99 ERA and a WHIP of 1.081. Pfeffer helped Brooklyn win the Pennant that year, and though they lost to Boston, with Pfeffer taking a Loss, he was solid in defeat.

Pfeffer slumped in 1917 and was in the Navy in 1918, only playing one Game that year. Upon his return to the Majors in 1919, he had two good years for Brooklyn, but a poor start in 1921 saw him traded to the Cardinals.

With the Robins, Pfeffer had a 2.31 ERA with a record of 113 and 80.

37. Van Mungo

Van Mungo was one of the most eccentric figures in Baseball, or would volatile be a better word?

Mungo did not have the luxury of playing for Brooklyn when they were a National League power, but that was no fault of Mungo, who went to four consecutive All-Star Games (1934-37). Known for an erratic fastball, heavy drinking, and a volatile temper, Mungo was the stuff of fables, but he was also a very competent hurler. His wildness was shown by leading the NL in Walks three times, but he also once led the league in Strikeouts and three times in SO/9.

Mungo's play fell off in the late 1930s, and was traded to a Minor League Team in 1941. With the Dodgers, Mungo went 102-99 with a 3.41 ERA.

38. Watty Clark

After a brief run in 1924 with the Cleveland Indians, it was back to the Minors for two years before the Brooklyn Robins signed Watty Clark.

In his second year with Brooklyn (1928), Clark proved he was there to stay, and he was a member of their starting rotation for the next four years as the top hurler on a mediocre team. Clark led the NL in FIP in 1929 and 1932, with the latter year seeing him earn his lone 20-Win Season.

Traded to the Giants during the 1933 Season, Clark was re-acquired by Brooklyn a summer later, but he only had one productive year in him before he rapidly declined and was out of the Majors after two Games in 1937.

For the Dodgers, Clark went 106-88 with a 3.55 ERA.

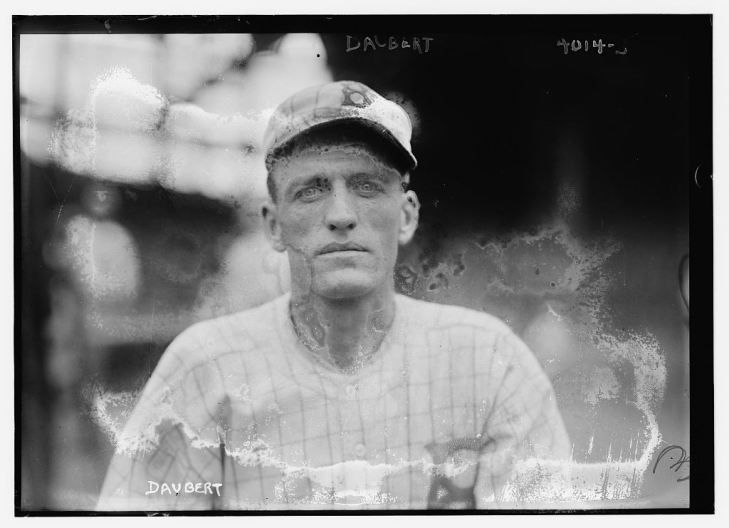

35. Jake Daubert

Jake Daubert initially thought that his first crack at the Majors would be with Cleveland, who signed him in 1908, but he never played there and was released shortly after. A second opportunity struck a year later with Brooklyn, and this time it stuck.

Playing at First Base, Daubert had a pedestrian rookie year, batting .264 with 146 Hits, but he then went on a six-year streak where he batted over.300. This included back-to-back Batting Titles in 1913 and 1914, with him winning the Chalmers Award, which was then the version of the MVP. He also exhibited solid speed, swiping at least 20 Bases in six of his seasons in Brooklyn.

Daubert was traded to Cincinnati in 1919, leaving Brooklyn with 1,387 Hits and a Batting Average of .305.

28. Dolph Camilli

Dolph Camilli began his Major League career with the Chicago Cubs, but it was his second team, the Philadelphia Phillies, where he proved that he was an everyday player. The Dodgers took notice and traded for him, feeling that he had another level in him. They were right.

Becoming a Dodger in 1938, Camilli led the NL in Walks that year and did so again in 1939, his first All-Star Game season. Camilli continued to smack Home Runs, belting at least 23 in his first two years in Brooklyn, with the latter two years seeing the First Baseman finish 12th in MVP voting, but the best was still ahead of him.

Camilli won the 1941 MVP when he led the NL in Home Runs (34) and RBIs (120) while going to his second All-Star Game. He had another good season in 1942, but the Dodgers saw that he was aging out, and he was traded to the New York Giants during the 1943 Season. Camilli refused to report to the Giants and would only play one more half-season in the Majors with the Red Sox in 1945.

With the Dodgers, Camilli batted .270 with 139 Home Runs and 809 Hits.

29. Johnny Podres

Johnny Podres was one of the most successful southpaws in Dodgers history, especially when you look at the postseason.

Debuting for Brooklyn in 1953, Podres came into his own in the 1955 World Series, winning the MVP of a 2-0 record and a 1.00 ERA over the Yankees. Podres had arrived, but he had to take a year off for military service, though he picked up right where he left off upon his return.

Podres led the NL in ERA (2.66), Shutouts (6), and WHIP (1.082) in what was arguably his finest season in baseball. He was still an integral player for years to come as the franchise moved to Los Angeles, earning All-Star trips in 1958, 1960, and 1962.

Sandy Koufax had become the undisputed ace of the Dodgers staff, but Podres was still a valuable commodity, with solid contributions in L.A.’s 1959 and 1965 Championships. Podres was traded to Detroit during the 1966 Season, but by that time, he was no longer a valuable member of the rotation.

With the Dodgers, Podres had a record of 136-104 with 1,331 Strikeouts.

21. Carl Furillo

A Dodger for the entirety of his career, Carl Furillo arrived in Brooklyn in 1946, and it did not take long before he became one of the Dodgers more popular figures.

Beginning in Center, Furillo was moved to Rightfield, where he was regarded as the master of comprehending the bounces of Ebbets Field. Furillo turned heads with arm strength, but he was an underappreciated hitter who won the 1953 Batting Title (.344), the second of two All-Star seasons. Furillo, who helped the Dodgers win two World Series (1955 & 1959), showed decent power, with six 15-plus Home Run years and an overall OPS of .813.

Furillo was released in May of 1960 while he was injured with a torn calf muscle, and he alleged that the team released him to avoid paying the higher pension rate affixed to a 15-year veteran, which he would have been had Furillo still been signed at the end of the season. Another MLB team never signed him, and it was a bitter end to one of the better runs in Dodgers history.

He exited Baseball with 1,910 Hits, 192 Home Runs, and a Batting Average of .299.

25. Don Newcombe

Don Newcombe was more than a great Pitcher; he was a trailblazer for African Americans in baseball.

After a brief time with Newark in the Negro Leagues, he was signed by the Los Angeles Dodgers. After a few seasons in their minor league system, Newcombe was called up for the 1949 season, making him the third black pitcher in the Majors. Newcombe proved his worth instantly, winning the Rookie of the Year with a 17-8 record and an All-Star Game trip. Newcombe was again an All-Star in 1950 and 1951 with a 19-11 and 20-9 season, respectively, but he was forced to leave the game temporarily.

Newcombe was drafted into the U.S. Military and went to Korea for two years. He came back and had a mediocre 1954, but he came back with a vengeance. Newcombe went 20-5 in 1955 and helped the Dodgers win their only World Series in Brooklyn. The following year, he went 27-7, leading the NL in Wins and WHIP (0.989), and he won both the Cy Young and MVP, making him the first player to do that in the same season.

That 1956 season was why he made it on the Baseball Hall of Fame ballot for 15 years. He never had anything close to an All-Star season again, and he played until 1960, finishing up with stints in Cincinnati and Cleveland. He retired with a 149-90 record, with a 123-66 with the Dodgers.

The Dodgers would honor Newcombe in 2019 as one of four names receiving plaques as "Legends of Dodger Baseball."

19. Dixie Walker

Dixie Walker was a bit of a late bloomer, having at one time been considered Babe Ruth’s heir with the Yankees in Leftfield to becoming a true baseball star in his late 20s, but nevertheless, he did become one.

Walker was plucked off of waivers from Detroit during the 1939 campaign, and while he showed flashes of greatness with his second team, the White Sox, he was still relying more on potential than accomplishment. Batting .308 with 171 Hits in his first full year as a Dodger, Walker again batted over .300 the year after, with both seasons earning him a top-ten finish in MVP votes.

With World War II taking many of Baseball's stars away, Walker was one of the few remaining, and he won his first and only Batting Title in 1944 (.357) and an RBI Title in 1945 (145). Walker continued to bat over 300, and as Baseball players returned from service, he was still a potent player, finishing second in MVP voting in 1946.

After one more good season, he was traded to Pittsburgh, but by that time, age had caught up to Walker, and he did not offer much to the Pirates.

As a Dodger, Walker batted .311 with 1,295 Hits.

18. Jim Gilliam

A member of the Dodgers throughout his entire Major League Baseball career, Jim Gilliam is one of the few players who won a World Series ring in both Brooklyn and Los Angeles.

Gilliam made an instant splash as the National League Rookie of the Year in 1953, where he led the NL in Triples (17) and had a career-high 125 Runs. Gilliam would have at least 100 Runs in the next three years and was twice an All-Star (1956 in Brooklyn and 1959 in L.A.). Gilliam performed his role as the Dodgers leadoff hitter, leading the NL in Walks in 1959 and having four 20 Stolen Base years. A member of four World Series Championship Teams, Gilliam was also an above-average defensive player at Second Base, and he led the NL in Total Zone Runs in 1956. Gilliam also had two top-ten finishes for the NL MVP.

While Gilliam might not be considered Hall of Fame worthy, he should have at least been on the ballot when he was eligible in 1972.

17. Roy Campanella

There is always one player on these top 50 lists that seem impossible to lock down. For the Dodgers that man is Roy Campanella, as he is a three-time MVP, but had they been judged in terms of current metrics, he likely would not have won any.

Before the Dodgers signed him, Campanella had played baseball in the Negro Leagues, Mexico, and Venezuela. Brooklyn's General Manager had Campanella and Jackie Robinson poised to break the color barrier. Robinson would shatter that ceiling in 1947, and a year later, Campanella joined the Dodgers.

Campanella had a promising rookie year but exploded the year after to emerge as the National League's top Catcher. An All-Star every season from 1949 to 1956, Campanella brought good power to the Catcher's position, smacking 221 Home Runs in that time, which, again, was not common by a Catcher in the 1950s. He also hit for average, having three .300 seasons. Due to his offensive prowess, Campanella was rewarded with the 1951, 1953, and 1955 MVPs, with the middle year being Campy’s best season. That year, he set a personal best in Home Runs (41) and led the NL in RBIs (142).

Defensively, Campanella was solid, leading all National League Catchers in Range Factor per Game nine times, and was also a five-time leader in Caught Stealing Percentage. He was also an anchor for their post-season success, with Campanella helping Brooklyn win the 1955 World Series and appear in four others.

In January of 1958, Campanella overturned his rental car when he struck a telephone pole. The ensuing accident resulted in a broken neck and the end of his baseball career. Campy left the Majors with 1,161 Hits, 242 Home Runs, and the promise of so much more.

Campanella was chosen in 1969 for the Baseball Hall of Fame in his seventh year of eligibility.

Again, if this rank does seem a little low, remember that the Dodgers ahead of him have much longer tenures than Campanella, though not all of them were as important.

22. Burleigh Grimes

Burleigh Grimes had a lot of great moments outside of Brooklyn, but the meat of his career took place with the team then named the Robins.

From Wisconsin, Grimes began his Major League career with Pittsburgh, where he noticeably lost 13 consecutive Games, so the Pirates fan base did not shed any tears when he was traded to Brooklyn after the 1917 Season. Grimes made an immediate impact with the Robins, going 19-9 with a 2.13 ERA in his debut season, and once the spitball was outlawed in 1920, he was grandfathered in and allowed to use it throughout the rest of his career.

An aggressive player on the mound, Grimes led the NL in Wins in 1921 (22) and was an innings-eater with four 300-plus Inning years. Grimes had a sub-standard year in 1925 (12-19, 5.04 ERA) and was marginally better in 1926. The Robins traded Grimes to the New York Giants, where he got back on track, but his Brooklyn record of 158-121 and a 3.46 ERA is good enough to place him on the top half of a baseball list, even as storied as the Dodgers. His rank is also propelled by his solid hitting, as he batted .251 with 227 Hits for the team.

Grimes was chosen by the Veterans Committee in 1964 to enter the Baseball Hall of Fame.