Even in his own band, Robbie Robertson, despite being the Band's lead guitarist, might not have stood out among his four other bandmates, or at least three of them, anyway. Bassist Rick Danko, drummer Levon Helm, and pianist Richard Manuel were the Band's lead singers, each with a distinctive voice that put its stamp on the stunning array of the Band's best songs—"The Weight," "Chest Fever," "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down," Up on Cripple Creek," "King Harvest (Has Surely Come)," "The Shape I'm In," and "Stage Fright" among others—and if organist Garth Hudson had kept the lowest profile among the quintet, Robertson wasn't that far above him.

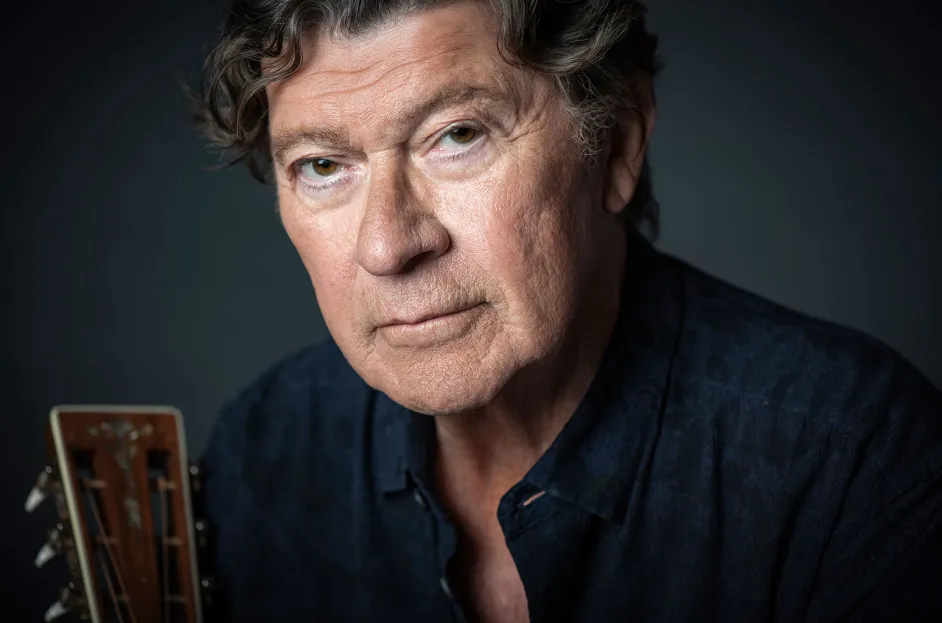

You can take a load off now, Robbie. You deserve to. Robbie Robertson, who carried the weight for the Band, died on August 9 at the age of 80. (Photo credit: Don Dixon, Billboard.)

Yet it was Robertson who quickly emerged as the Band's principal songwriter—he penned all the songs listed above—with his voice coming through the material his bandmates sung. As heard in his lyrics, Robertson's voice was a distinctive one that brought Americana into the realm of rock music without mockery or contempt nor with nostalgia or sentiment, instead establishing a continuum of cultural and historical storytelling that could blend the past, lyrically and instrumentally, into the present without sounding artificial or contrived. And the final irony is this: Robertson, along with his fellow Band members excepting Helm, was a Canadian.

When You Awake

Born in Toronto, Ontario, on July 5, 1943, to a First Nations mother and a Jewish biological father, his mother having married another man named James Robertson, Robbie learned guitar from his mother's relatives and soon became an avid listener to rock and blues music played on American radio stations south of the Canadian border. By his teens he was forming his own rock bands in the Toronto area.

In the late 1950s, American rockabilly singer Ronnie Hawkins ventured into Canada and soon found the territory to his liking. Like countless others, Hawkins was inspired by Elvis Presley, but he was shrewd enough to realize that he would never be more than a competent imitator and chose to become a big fish in the relatively small Canadian musical pond. (Hawkins remained in Canada until his death in 2022.) Having seen Robertson's band the Suedes perform at a Toronto club, he was impressed sufficiently to sit in with them for a few numbers.

Duly encouraged, Robertson offered Hawkins a pair of his original songs to record in 1959; soon he was part of Hawkins's road crew before becoming a backing musician himself. Robertson also befriended Hawkins's drummer Levon Helm, and it was while visiting Hawkins and Helm in their native Arkansas that Robertson became enamored of Southern history and culture that would manifest itself in songs such as "King Harvest (Has Surely Come)," "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down," and "Up on Cripple Creek."

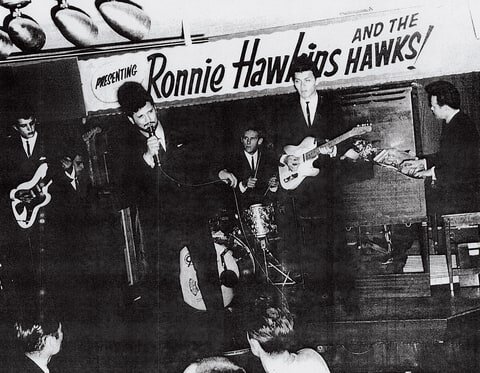

As attrition began to erode Hawkins's backing band, named the Hawks, he filled the vacancies with local talent. By 1961, three of Robertson's fellow Ontarians had become Hawks: bassist Rick Danko and pianist Richard Manuel quickly signed on, but organist Garth Hudson, formally trained in music theory, was initially reluctant to join a band playing raw and novel rock and roll until they agreed to pay him for the weekly music lessons he taught them. Thus constituted, the quintet honed their stagecraft playing behind the popular Hawkins.

The Band began as the Hawks, backing American rockabilly singer Ronnie Hawkins. Levon Helm plays drums.

Talented musicians all, with Manuel and Robertson harboring compositional ambitions, the Hawks eventually outgrew Hawkins's rockabilly formula frozen in time, and by 1964 they had left their early benefactor and lit out as Levon and the Hawks. Their constant gigging had already begun to pay dividends: By 1965, they had come to the attention of Bob Dylan.

Already a folk sensation, Dylan itched to break free of that form's elementary strictures and, having already "plugged in" with a rock-oriented band, such as the impromptu aggregation he formed at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival that ruffled the feathers of folk purists—a harbinger of what was to come—he wanted the Hawks to accompany him on a world tour that would begin in late 1965 and continue on through 1966. For their part, the Hawks knew of Dylan, but only as a folk artist, and they were largely unaware of just how popular he had become internationally. They were in for a rude awakening.

Dylan's concerts for the tours began with a solo set before he returned to the stage with the Hawks. While audiences got what they expected from Dylan's solo acoustic numbers, the electric sets with the Hawks incited negative reactions that became downright hostile. For the Hawks, even their years of steady gigging with Ronnie Hawkins couldn't prepare them for the reaction they faced over the months of touring with Dylan. Levon Helm couldn't take it; he left the tour after only a month, with a series of drummers replacing him. Dylan and the remaining Hawks responded with fiery defiance, conjuring up a raw, biting sound, often keyed to Robertson's knife-edged lead guitar, that pushed Dylan's rock, now more than simply electrified folk-rock, to the limit.

The Hawks felt the heat backing Bob Dylan (left) during his tumultuous tours in 1965 and 1966. Robbie Robertson trades licks with Dylan. (Photo credit: Getty Images.)

One show at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester, England, in May 1966 yielded one of the most famous bootleg recordings in rock history, capped by an audience member shouting "Judas!" at Dylan, who replied, "You're a liar. I don't believe you," then turned to the band and instructed them to "play it fucking loud" before they tore into "Like a Rolling Stone." (That concert recording, for years erroneously identified as being at London's Royal Albert Hall, was officially released by Columbia in 1998 as The Bootleg Series Vol. 4: Bob Dylan Live 1966, The "Royal Albert Hall" Concert.)

Across the Great Divide

In July 1966, Dylan was injured in a motorcycle accident and retired to Woodstock, where he was joined the following year by the Hawks, staying in nearby West Saugerties. However, before the area would become immortal for its 1969 Woodstock music festival, it was the site for rock history made by Bob Dylan and the Band, the name the Hawks adopted because of the locals, who always referred to the five musicians who had rented the big pink house in which they rehearsed and recorded simply as "the band." (That's the story they stuck to, anyway.)

With Dylan, the Band recorded a wealth of breathtaking tracks that Dylan would release in 1975 as The Basement Tapes (Columbia), which would also include songs written by Manuel and Robertson both singly and together. But before audiences would hear that monumental work, the Band in 1968 released its debut album, Music from Big Pink (Capitol), that introduced the world to one of the most instrumentally accomplished and lyrically evocative rock bands yet heard.

Paradoxically both revolutionary and retrospective, Big Pink bore little, if any, resemblance to the psychedelia or heavy rock of the period; instead, the Band looked backward to draw on a virtual encyclopedia of musical styles—folk, bluegrass, country and western, rhythm and blues, and rock and roll—for its inspiration. This studied eclecticism lent the band the maturity to lead its generation into the next era of rock and roll.

Of the album's eleven songs, Robbie Robertson composed four including "The Weight," often considered to be the Band's signature song; it appeared on the soundtrack to the 1969 Peter Fonda-Dennis Hopper hippie-biker classic Easy Rider, an iconic Sixties-counterculture movie with the enigmatic refrain from "The Weight"—"Take a load off, Fanny/Take a load for free/Take a load off, Fanny/And you put the load/You put the load right on me"—seeming to encapsulate, and perhaps gently mock, the woozy philosophizing of the psychedelic era, a suggestion underscored by the rustic instrumentation slowly but inexorably driving the lyrics, a reminder of the roots from which the flower-power generation had sprung.

Praise for the album sprung from musicians including Eric Clapton, George Harrison, and even Pink Floyd's Roger Waters, indicating the broad appeal Big Pink engendered, and although it didn't spawn any hit singles ("The Weight" came the closest, reaching Number 63 on Billboard's Hot 100 Singles chart), it quickly became an essential album for serious pop music fans.

The Band's next album, The Band (Capitol, 1969), may be even better, if only because it had the focus and cohesiveness of a concept album without sounding overtly, and thus pretentiously, like a concept album. Credit for that goes to Robertson, who wrote eight of the album's dozen songs himself while co-writing the other four, three with Richard Manuel and one with Levon Helm.

That concept, glimpsed on Big Pink in fragmented form in songs such as "Tears of Rage," "The Weight," and a cover of "Long Black Veil," popularized by Lefty Frizzell in 1959 before becoming a county-music standard, was an appreciation of America, its history, its culture, its contradictions, that avoided superficial populism or overt patriotism but instead delivered a complex, nuanced, highly personal observation from the perspective of an informed outsider, epitomized in Robertson's opening track, "Across the Great Divide."

The Band when the going was good. L-R: Garth Hudson, Robbie Robertson, Levon Helm, Richard Manuel, Rick Danko. (Photo credit: Gijsbert Hanekroot.)

Like many of their Canadian musical contemporaries such as Gordon Lightfoot, Joni Mitchell, and Neil Young, the four Canadian members of the Band experienced America before they even began visiting their "neighbour" to the south as the backing musicians behind Ronnie Hawkins and Bob Dylan, both American artists.

Robbie Robertson's experience of hearing American rock and blues on his radio in Ontario is hardly unique. Even now, the great majority of Canadians live within one hundred miles (or, if you prefer, about 166 kilometres) of the US-Canadian border. Canadians grow up with American culture alongside our home-grown heritage; it is so ingrained that we hardly think twice about it.

I say "our" and "we" because even though I'm a long-time American now, I came here from Canada, and when I attended grade eleven in Victoria, British Columbia, we had to take one year of American history. We all grumbled about it, but it was obvious why, given the profound influence the United States exerts on Canada socially, culturally, economically, and to a large extent politically as well, we had to take it.

So when, after a few years of being in the States, I discovered the music of the Band, songs such as "Across the Great Divide" naturally resonated with me. I won't pretend that I understood why at the time, but instinctively I identified with that "cross-border sense," if you will, which also sneaks into Richard Manuel's "We Can Talk," from Big Pink: "But I'd rather be burned in Canada/Than to freeze here in the South."

Yet Robertson's songs for The Band, many of which are vivid picaresques ("Jemima Surrender," "Rag Mama Rag," "Up on Cripple Creek"), tell their stories from a personal point of view, forgoing Big Statements and instead letting the choice details accrete into a larger picture. This is true in what is arguably the album's most controversial song, "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down," delivered from a Southerner's perspective that elicits sympathy even as the Confederacy crumbles before his eyes. That didn't stop Joan Baez, no stranger to political controversy, from garnering a Number Three hit with her 1973 cover of the song.

Indeed, although the Band did snag its first Top Forty hit with "Up on Cripple Creek," which peaked at Number 25, it was becoming clear that this quintet, so talented instrumentally—and all were multi-instrumentalists—and now with Robertson providing focused, evocative lyrical narratives, was not going to be a pop band issuing a string of hit singles but rather a serious musical ensemble whose albums unfolded into a rich array of exquisitely crafted songs, on the forefront of the album-oriented approach that burgeoned in the 1970s.

Stage Fright

Yet the Band faced another problem besides name recognition among the mass of pop-music fans. Despite years of touring both with Hawkins and especially with Dylan—whose harrowing shows were the Band's baptism of fire before they ever became the Band—the band, even after releasing the superlative Music from Big Pink, with The Band recorded and ready to be released in September 1969 as both albums would soon be enshrined in the classic-rock canon, had yet to take the stage as the Band.

And when it did, at the Winterland Ballroom in San Francisco in April 1969 (which is where The Last Waltz would be filmed seven years later), with the Band no longer the backing unit but having to face the audience directly, it choked. According to Greil Marcus's account in his classic Mystery Train: Images of America in Rock 'n' Roll Music, the Band's first gig was a disaster that incited the eager crowd entranced by the quintet's brilliant debut album to the kind of reception they had experience with Dylan, and although they rebounded the next night, Marcus speculates that their painful premiere instilled into them an inherent conservatism that would continue to hamper them for the rest of their career.

That conservatism can be felt in the Band's next album, Stage Fright (Capitol, 1970), as the roots- and traditional exercises became dissolved into a more standard rock-oriented musical approach. Moreover, many of the songs, all written by Robertson with Manuel co-writing two and Helm one, evinced the weariness of touring life on the road—on "Time to Kill," "Stage Fright," and especially "Just Another Whistle Stop," the titles alone tell the story.

But if Stage Fright was disappointing, Cahoots (Capitol, 1971) was a disaster, at its worst a pale imitation of a band trying to sound like the Band. Again Robertson did the lion's share of the writing although Danko and Helm helped him write "Life Is a Carnival," the only salvageable song apart from a cover of Dylan's "When I Paint My Masterpiece."

What followed was retrenchment and confusion. Falling back on its strength, live performances, the Band released the concert album Rock of Ages (Capitol, 1972), a sterling set yet an obvious holding action that yielded the Band's second, and last, Top 40 hit with a live cover of Marvin Gaye's "Don't Do It," while offering Robertson's previously-unreleased "Get Up, Jake," another enjoyable, if modest, slice of Americana.

Also part of the Americana was Moondog Matinee (Capitol, 1973), comprising all cover versions of older rock and R&B songs that showcased Helm and Manuel as singers, particularly Manuel's showstopping rendition of the Platters' "The Great Pretender," although Robertson contributed additional lyrics to "Mystery Train," Junior Parker's evocative R&B dirge that Elvis Presley souped up for his epochal Sun sessions, that only added to the enduring mystique of this haunting song propelled by the Band's precision-tuned rhythmic drive.

In fact, critic Greil Marcus borrowed the song's title, not to mention its imagery, for his own epochal work Mystery Train: Images of America in Rock 'n' Roll Music, first published in 1975, in which this American Studies major from UC Berkeley maps musical innovators—"ancestors" both famous (Robert Johnson) and obscure (Harmonica Frank) and their "inheritors" the Band, Sly Stone, Randy Newman, and Elvis Presley—to his crazy-quilt conception of America (or maybe it's the idea of America?) and makes it sing. Marcus even claims that Robertson once said about The Band that you could have called that album America.

In "Pilgrims' Progress," his essay on the Band, Marcus, after praising the first two albums to the skies, notes that the band's disastrous first gig inevitably compelled them to "hedge their bets" as "in every sense, the kind of unity that had given force to those first two albums, and to the idea of the Band itself, was missing." He reports that as the band began to fall apart, Robbie Robertson took it over in order to save it.

The Unfaithful Servant

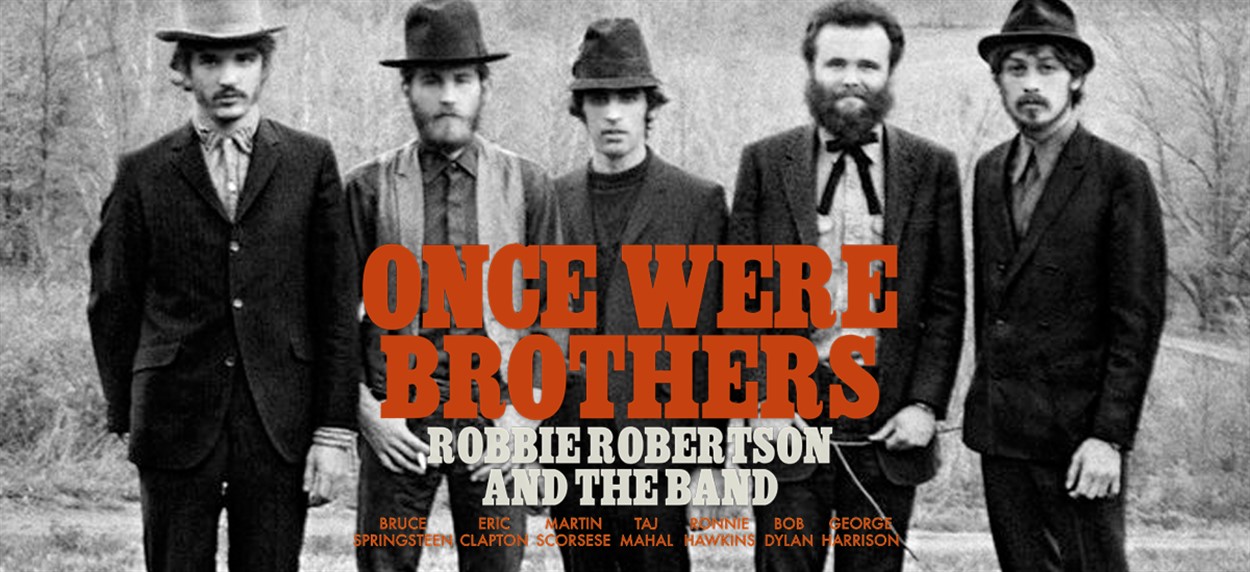

Indeed, decades later, in 2016, Robertson released his autobiography, Testimony, in which he reveals that while he was diligently composing material for the band, Danko, Helm, and Manuel were too busy partying to excess, harming themselves and the band's subsequent growth. This becomes the central theme in Daniel Roher's 2019 documentary movie Once Were Brothers: Robbie Robertson and the Band.

And while prominently-featured Robertson receives corroboration for these claims from his ex-wife Dominique Bourgeois and former road manager Jonathan Taplin, the three guilty parties have no such recourse. By the time the documentary aired, Manuel, Danko, and Helm were already dead, and Once Were Brothers has no surrogates for any of them to speak on their behalf, although it is true that substance abuse, particularly in Manuel's case, was well-known among the three.

The 2019 documentary Once Were Brothers paints Robertson as the diligent one while Danko, Helm, and Manuel all partied to excess. All were already dead when the movie was released.

Moreover, Hudson, now the sole survivor of the Band's original members (ironically, he is the oldest of the five and is now 86) is seen only in archival footage and appears never to have made any public comments on this matter, leaving Robertson's the only testimony extant. (In 2002, Robertson had bought out Hudson's interest in the Band, as he had Danko's and Manuel's.)

In 1973, Robertson moved from the artists' conclave of Woodstock to Malibu, just north of Los Angeles, where he reconnected with Bob Dylan living nearby. Soon the rest of the Band came west to help the pair work on Dylan's next album, Planet Waves (Asylum, 1974). Best-known for the sentimental lullaby "Forever Young," the album was an improvement over Dylan's middling recent efforts although this was hardly a reprise of the still-to-be-released The Basement Tapes.

However, Dylan, who had not done any touring since he'd had his motorcycle accident (barring one-off appearances such as George Harrison's 1971 The Concert for Bangladesh, an early rock benefit concert), planned a US-Canadian tour for early 1974 with the Band backing him. Intense fan interest in the tour spilled over into the shows themselves, which found Dylan, ostensibly promoting his new album Planet Waves, playing hardly any songs from it, instead delivering drastically revamped reappraisals of his earlier material.

Fired up by Dylan's fervor, the Band responded with equal passion, unleashing a firestorm that surpasses its not-inconsiderable playing on Rock of Ages, with Robertson's piercing guitar prominent in the mix, particularly on Dylan's "All Along the Watchtower," done as an electric arrangement that nods to Jimi Hendrix's immortal cover version. Released originally as a two-LP live set, Before the Flood (Asylum, 1974) captures some of those fireworks while suggesting what the intensity must have been like when the Band, then known as the Hawks, had backed Dylan on the legendary and contentious (and still-unreleased officially) world tour nearly a decade previously. The Band has one side of this outstanding concert set to itself and even serves up the previously-unreleased delight "Endless Highway," penned by Robertson.

But once that euphoria wore off, the Band returned to its doldrums. The quintet released Northern Lights – Southern Cross (Capitol) in 1975, with all material written by Robertson, whose "Acadian Driftwood," "Ophelia," and "It Makes No Difference," the best of the lot, can only echo the spirit and inventiveness of their predecessors while the last title seemed to sum up what had happened to the Band's collective attitude.

The Weight

By 1976, Robertson, who in the popular perception advanced by the rock press essentially was the Band, with the others his supporting cast, decided to call it quits. Thus was born The Last Waltz, which in turn became the Band's final concert at San Francisco's Winterland Ballroom, where its disastrous first-ever show as the Band had struck a blow from which it seemingly never recovered; the concert movie filmed by Martin Scorsese, whose own star was rising with the successes of Mean Streets (1973) and Taxi Driver (1976); and the soundtrack album that presented in their entirety the songs by both the Band and the galaxy of guest stars who, in all fairness, eclipsed the spotlight act, which for one night became the greatest backing band in classic-rock history.

Initially, the concert was to be held at Oakland's Paramount Theater, but with sagging ticket sales indicating a half-full venue, concert promoter Bill Graham arranged a switch to the Winterland for Thanksgiving Day that included a full Thanksgiving dinner—and even that was not enticing enough until Graham leaked the list of the "special guests" who, as Robertson put it in the movie, were some friends who helped them take it home.

The Last Waltz marked what would become a lasting friendship and partnership between Scorsese and Robertson, who would work with Scorsese on many of the celebrated director's best-known projects from Raging Bull (1980) and The Color of Money (1986) to Casino (1995) and The Irishman (2019).

A last waltz but a new beginning for Robertson, who worked with The Last Waltz director Martin Scorsese right up until his death. (Photo credit: George Pimental, Getty Images.)

Thus, it is perhaps not surprising—not to mention suggestive of the varying regard accorded to the individual Band members—that, during the interview segments interspersed throughout the night's musical performances, it is Robertson who clearly emerges as the center of attention: Rock-star handsome, sharply dressed, articulate and charming, Robbie owns The Last Waltz although Levon Helm, who is next in terms of interview time, seems cast as his foil, his prominent Arkansas accent contrasting with Robertson's urbane tones.

Yet Helm, who repudiated his involvement in The Last Waltz and was critical Robertson's role in it, is nobody's fool. He makes his own distinctive impression as his canny perceptiveness punches through those seemingly cornpone observations. Unfortunately, the other three get the back of the hand. Relegated to the margins, Rick Danko, Garth Hudson, and Richard Manuel come across as rustic yokels, barely articulate, with Manuel describing the shoplifting the band sometimes committed in its early, hungry days as if he were a schoolboy bragging before he had to go face the consequences, although Danko manages a hipster slickness at times.

Probably because of The Last Waltz, Helm also found work in Hollywood. His feature-film acting debut came portraying Loretta Lynn's father in the biopic Coal Miner's Daughter (1980) before he provided narration for The Right Stuff (1983) while performing a supporting role in that space-program epic of the Mercury astronauts based on Tom Wolfe's best-selling account. A born performer, Helm launched a lengthy solo musical career that saw him recording albums and maintaining a steady touring presence right up until his death in 2012.

While Robertson had floated the idea that the Band, similar to the Beatles and Steely Dan, could continue to record music in the studio without having to tour, the five never played together again as a unit although they did occasionally collaborate on each other's solo projects.

The Band did release a studio album, Islands, in 1977, but not only was it strictly a contractual obligation to Capitol Records, it comprised material dating back to 1972 that had never been released; however, anyone expecting a reprise of the Who's Odds and Sods, a similarly-assembled collection that wound up exposing some essential Who statements (notably "Long Live Rock" and "Pure and Easy"), will be sorely disappointed, with only the Richard Manuel-sung cover of "Georgia on My Mind" notable, and that primarily because the Band had recorded it in support of Jimmy Carter's successful 1976 presidential bid.

Sans Robertson, the Band did reform under that name for concert appearances starting in 1984, but Richard Manuel's suicide death in 1986 while on tour ensured that the once-were-brothers would never again perform as one. By the 1990s, the Band was recording albums, releasing a trio between 1993, all of which drew overwhelmingly on outside sources for material, before Rick Danko died in 1999.

Endless Highway

As for Robertson, he released his first solo album in 1987, nearly a decade after The Last Waltz had been released. Having become the prime mover in the Band, particularly because of his songwriting, expectations ran high for the self-titled album, released on Geffen Records, that Robertson had co-produced with Daniel Lanois, at the time a very much in-demand producer who had worked with Brian Eno, Peter Gabriel, and U2, helping to push those last two to the forefront of 1980s pop.

Although the neo-classic rock of "Showdown at Big Sky," with the BoDeans' Sam Llanas and Kurt Neumann combining to provide eerily Rick Danko-like backing vocals, swaggered across the radio waves for a few weeks, Robbie Robertson proved a puzzling disappointment.

The Band's leader had kept up with then-contemporary musical trends, but the flood of guest artists eventually relegated Robertson and his distinctive if limited singing voice to just another player in the band. "Fallen Angel," ostensibly an elegy to Richard Manuel, ultimately sounds like a track by its guest vocalist, Peter Gabriel; the same fate befalls Robertson's collaboration with U2, "Sweet Fire of Love," with Lanois's production approach sealing that fate on both tracks.

Moreover, Robertson's flair for evocative lyrics is absent; instead, he resorts to cliché phrases and clunky metaphors (most egregiously in "American Roulette," a trite tribute to James Dean, Elvis Presley, and Marilyn Monroe) that cry out for a drum roll and a basso profundo voice announcing each song except for "Somewhere Down the Crazy River," on which that would only elicit giggles considering how pretentiously silly that song is. Buried in the busy mix are brief contributions from former Band mates Rick Danko and Garth Hudson.

That didn't stop Robertson from releasing Storyville (Geffen) four years later, with its concept centered around the American South, particularly the famed titular New Orleans red light district, which set him up for more claims to pretentiousness. Robertson released three more solo albums, with 1998's Contact from the Underworld of Redboy (Capitol) blending Canadian Aboriginal musical forms with rock, trip-hop, and electronica.

In a very real sense, that gets to the heart of Robertson's musical intelligence: mining the past and establishing a continuum with the present. It was the approach he had taken with the Band for its debut album Music from Big Pink a half-century earlier, when he had been just 25 years old—and already a veteran of the rock and roll scene for a decade. When the Band called it quits in 1976, the members had already garnered a lifetime of experience before they had even turned forty. Although The Last Waltz wound up spotlighting Robertson, with Helm a step behind, all five, even if it was just in their playing and not in their speech, seemed wise beyond their years.

The Shape I'm In

I can't tell you how many times I've seen The Last Waltz simply because there were times when I watched it that I was so blitzed that the next day I didn't even recall having seen it the night before. This was a period in my life when The Last Waltz was one of the default movies my friends and I watched while we were partying, and like the reputed behavior of Danko, Helm, and Manuel, my partying proved to be a detriment to any useful or constructive activity.

Made in the late 1970s, when cocaine became the drug of choice for the entertainment set, The Last Waltz does contain more sniffling by the participants than the average concert film; whether Neil Young's segment, singing "Helpless," had to be edited in post-production to remove traces of white powder from his nose may or may not be urban legend. And if I take the Fifth on whether I myself had been guilty of ingesting Peruvian Marching Powder while watching The Last Waltz years later—well, I think the legal types would call that nolo contendere. It was a bad-crazy time for me that no one else is likely to care about, but even the mention of The Last Waltz launches blurred images of that combustible time into my mind's eye to this day.

Fortunately, I don't get flashbacks when I watch it now or listen to the songs from the soundtrack album. The Last Waltz endures as a concert movie, as a celebration, as a farewell, as an embarrassment of riches, and as a passing of the torch to a new generation of rockers. Punk was already ascendant when the concert itself occurred, and it was establishing itself as the new order when the movie was released.

The embarrassment of riches, of course, is the lineup of legends who turned up to bid the Band adieu. This includes former boss Ronnie Hawkins, who had already seen his charges become the next generation of rockers to supersede his musical style that seemed superannuated two decades later, although that doesn't hamper his rowdy rendition of "Who Do You Love," with Robertson's fiery guitar revelatory in the 1963 version Hawkins cut, and still potent here.

Another former boss was Bob Dylan, whose last-minute decision not to be filmed, which would have been disastrous—Warner Bros. agreed to finance the movie only if Dylan appeared in it—managed to get reversed, and although the intriguing, unusual medley he and the Band perform, beginning with "Baby, Let Me Follow You Down" and segueing into "I Don't Believe You (She Acts Like We Never Met)" and "Forever Young" before reprising "Follow You Down," lacks the feistiness they display on Before the Flood; well, Dylan does start to get pugnacious at the end of the reprise, with Robbie's guitar heating up as well.

Bob Dylan (center) rocking out with Rick Danko (left) and Robertson in The Last Waltz. Yet Dylan nearly derailed the legendary concert movie while it was still being filmed.

In fact, excepting Levon Helm's spirited vocals on "Up on Cripple Creek," his raucousness shared briefly by Rick Danko, and a few other moments here and there, the Band itself feels perfunctory on its own material. It takes the guest stars to jump-start the Band, whether Van Morrison conducting the players on "Caravan," Robertson dueling with Eric Clapton—especially when Slowhand suddenly loses his guitar strap and Robbie has to jump in with an impromptu fill—on "Farther on up the Road," and, in what remains a supremely transcendent moment, Paul Butterfield's duet with Levon on a steaming, locomoting "Mystery Train" that seems to electrify the entire Band.

The Last Waltz has proved to be a landmark, influential movie, and not always in a positive sense. Promoter Bill Graham—surely a polarizing figure throughout his long career in the rock biz, although the Winterland was his venue and he is credited with getting Dylan to change his mind and thus save the project literally at the eleventh hour—had procured stage trappings from the San Francisco Opera's production of La traviata, which seem overly ornate for a group that conjured up a rustic feel in its music.

Moreover, the movie's portentousness provoked both imitation and parody. For its 1988 concert movie Rattle and Hum, U2 took the pensive moodiness of The Last Waltz to pretentious extremes, even filming it in black and white, while engaging a Harlem gospel choir, B.B. King, and even Bob Dylan as guest stars. (During a run-through of "When Loves Comes to Town," an international hit that featured King, he remarks, "You mighty young to write such heavy lyrics.")

So much for the imitation. Now for the parody. Using The Last Waltz as their template, Christopher Guest, Michael McKean, Rob Reiner, and Harry Shearer scripted the quintessential mock rock documentary (better known by its portmanteau "mockumentary") This Is Spinal Tap (1984), which took the mickey out of the pomposity of rock and roll in its many guises with such loving—and knowing—strokes that you know these guys see poking fun at rock's grandiose tendencies as all part of the grandiosity. (And considering that Spinal Tap itself became a franchise, they might be guilty of such grandiosity themselves.)

Reiner even narrates the movie as director "Marty DeBergi," a direct swipe at Martin Scorsese, and you just know he must have been studying Scorsese's interview segments in The Last Waltz for the hilarious exchanges he has with the Tap players. And it's probably no coincidence that Tap's long and winding rock and roll road, at least as depicted in This Is Spinal Tap, seems to echo that of the Band's.

To Kingdom Come

For years now, I've watched very little television, but a couple of years ago, late at night, I did have it on and was idly flicking through the channels when I had to go back a channel or two. I was right. I thought I'd seen Robbie Robertson. He was on some interview show, a small stage, a small studio audience, some young guy I didn't recognize interviewing him, but it was Robbie Robertson.

I can't recall now what he was talking about. It didn't matter. He was still the charming raconteur, spinning his yarns in engaging tones and a practiced, confident narrative. I sat there enthralled, not so much by what he was relating as by the way he held the audience's attention. From what I could see, it was closer to the young kid's age than the expected bluehairs and graybeards of Robbie's generation, and I was oddly elated that he had connected with them.

That was what Robbie Robertson did, and, through his music, still does: connect. He told stories, the best of which can hold your attention even after hearing them countless times. Some, like "The Weight," have a cast of characters—Miss Fanny, Miss Moses, Carmen and the Devil, Young Anna Lee, Crazy Chester—to rival a Bob Dylan or a Bruce Springsteen song.

Others, like "King Harvest (Has Surely Come)," tell a tale that is both evocative:

and compelling:

Still others, like "Across the Great Divide," wry and lugubrious:

Robbie Robertson has gone to his last waltz. I will miss him. Then again, I won't, since he will live forever in his music. I'll just have sadness leaven my delight from now on. But I'll still play this movie loud.

Amen to that, Robbie. This opening title card from The Last Waltz will serve as a testament to Robbie Robertson's amazing music.

Comments powered by CComment